THE MULLENDORE MURDER

By Mike Easterling

If not for the circumstances, it could have been a perfectly enjoyable Sunday drive.

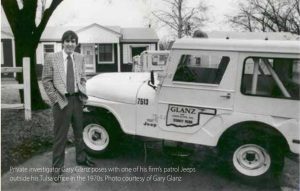

On the morning of September 26, 1970, Gary Glanz, a 30-year-old private investigator from Tulsa, found himself headed north on U.S. Highway 75 through the Oklahoma countryside. It was a warm, clear day that still felt more like summer than early fall.

But the idyllic scene was spoiled by the solemn, even fearful, mood in the car. Glanz was traveling with a woman named Linda Mullendore and one of her attorneys, John Arrington. Arrington had awakened Glanz early that morning with a phone call and retained Glanz’s services on his client’s behalf. The woman had learned hours earlier that her estranged husband of 11 years, millionaire E.C. Mullendore III, had been shot dead the night before on his ranch.

Arrington had explained to Glanz that E.C. Mullendore had been insured for $16 million, but was heavily in debt and had become involved with unsavory characters from the Kansas City, Missouri and St. Louis areas. Glanz was summoned to provide security for the woman and her children.

The investigator moved quickly, calling his contacts at the Tulsa Police Department and asking to have officers sent to Linda Mullendore’s home.

Now, with that issue addressed, he found himself escorting the woman and her lawyer to the scene of the crime, the Cross Bell Ranch. The ranch was tucked away in a remote corner of sprawling Osage County in northern Oklahoma. At approximately 42,000 acres, it was one of the largest spreads in Oklahoma and home to thousands of head of cattle, bison and quarter horses.

Everything about the Cross Bell was well kept and first class, illustrating the Mullendore’s fondness for life’s finer things. Glanz soaked it all in as the car rolled past the gates for four miles until it reached the family compound.

The Cross Bell had been, until a few days earlier, home to Linda Mullendore and her four children. The 33-year-old native of nearby Pawhuska—a statuesque, dark-haired beauty with a regal air who bore more than a passing resemblance to Hollywood icon Elizabeth Taylor—had become E.C. Mullendore’s sweetheart when they were both in their early teens and married him in 1959. But their relationship became strained as E.C.’s financial difficulties multiplied and his drinking increased.

Relatively small in stature, the feisty E.C. was nevertheless no stranger to brawling, particularly after he’d been emboldened by a few hours of drinking. Linda watched his boozing with dismay and noted how it transformed her formerly even-tempered and highly focused husband into a mercurial, paunchy loudmouth. After the two had an intense verbal exchange a week earlier, Linda decided she had had enough.

She gathered up the children and fled the ranch, moving to Tulsa and filing for divorce on September 23. But an unknown assailant, or assailants, rendered that decision moot a little more than 48 hours later by firing a shot into E.C. Mullendore’s forehead.

Even at this early stage, Glanz realized he was fascinated with the case, which drew enormous media attention. What he didn’t know that morning was that his investigation into the crime would come to consume him for much of his life, requiring 40 years of detective work before the mystery would be fully unraveled.

Professionalism was Lacking

The scene at the compound, as Glanz recalled, was like a circus. Along with the representatives of the Osage County Sheriff’s Department and the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation who were working the crime scene, there were officials from the nearby Washington County Sheriff’s Department and the Bartlesville Police Department present—mostly as sightseers, Glanz said.

Glanz found it difficult to keep his curiosity in check as the day progressed, as he was aching to get a look at the crime scene. He also recalled being struck by the rawness of the young Osage County deputies. It was clear, he thought, that many of them had no idea what they were doing—a disturbing prospect, considering the gravity of what had occurred.

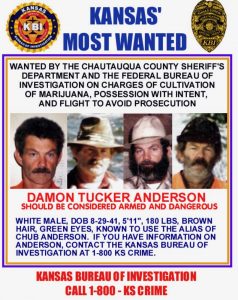

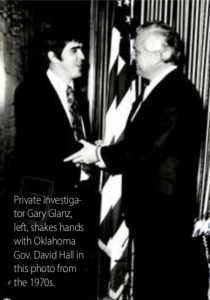

That lack of professionalism bothered Glanz, a decorated former Tulsa police detective. But since he was not at the ranch in an official capacity, he had no access to the crime scene—the basement of the so-called Little House, a smaller residence where E.C. had lived, until recently, with his wife and kids. The rancher had been reported shot the night before by his driver, a horse-rustler-gone-straight named Damon Tucker “Chub” Anderson.

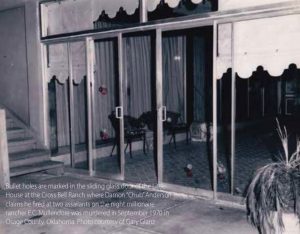

Anderson said he was upstairs at the residence when he heard a shot. He claimed he raced downstairs to find his employer on the floor and was trying to examine him when he was shot from behind in the right shoulder. Anderson said he saw two stocky young men in suits race up the stairs behind him. Despite his injury, he said, he gave chase, squeezing off five or six rounds from the .25-caliber handgun he carried as the men escaped through a sliding glass door.

Anderson told authorities he then staggered to the nearby residence of ranch manager Dale Kuhrt, alerting him to the crime. While Anderson climbed into his car and set out for the hospital to be treated for his wound, Kuhrt summoned the neighboring Washington County Sheriff’s Department, though the incident had taken place in Osage County.

A deputy and a pair of ambulance attendants responded, deciding after a brief discussion to load Mullendore into an ambulance. They sped back to the hospital in Bartlesville, but it was an unnecessary trip. Mullendore was dead all right. He had been shot in the forehead after apparently having been in a pitched physical battle, as evidenced by the lacerations to his scalp, the contusions to his face and some loosened teeth.

The next day, while Linda Mullendore met with her in-laws, Glanz engaged the deputies in conversation and began piecing together the situation. An experienced interrogator with a gift for putting people at ease, Glanz learned that the Cross Bell had fallen on hard times after E.C. initiated a series of expensive improvements and went on a land- and livestock-buying spree. All told, he owed nearly $10 million.

In an effort to stave off his creditors, E.C. had been trying to solicit a sizable loan from reputed organized crime figures, who had become a regular presence at the Cross Bell. That led to speculation among lawmen and local residents alike that E.C.’s murder was a mob hit. Anderson’s description of the previous night’s events seemed to support that version of events.

Glanz wasn’t buying it. He quickly deduced the prime suspect was the 29-year-old Anderson, who had worked at the Cross Bell for approximately four and a half years as a driver, babysitter, handyman, ranch hand and, by some accounts, E.C.’s bodyguard.

Even as he arranged for around-the-clock security for Linda and her children, it was becoming increasingly apparent to Glanz that the mob had nothing to do with E.C. Mullendore’s death and that his widow was in no danger. He dismissed Anderson’s tale, labeling it a “John Wayne story,” too heroic to be true.

Glanz returned to the ranch by himself a day before the September 29 funeral and engineered his first meeting with Anderson, who was fresh out of the hospital. Despite his suspicions, Glanz liked the handyman immediately, later recalling that Anderson had a mischievous smile to go with his habit of looking people directly in the eye.

Anderson and Glanz hit if off, leading to several more meetings between the two. Glanz’s official involvement would last for about a year and a half, evolving into a full-fledged investigation of the killing and leading him to pursue leads in Kansas City, New Orleans and Seattle. But the message from those paying his fee was clear, Glanz said, “Let’s get the insurance money, then we’ll worry about solving the crime.”

Hinting at Something More

Meanwhile, Glanz felt himself moving into the role of adviser and confidant for the handyman. The private investigator recalled getting a call from a worried Anderson two weeks after the incident as media reports surfaced indicating that an arrest in the case was imminent. Anderson phoned Glanz that morning, asking him to meet to discuss the situation.

Glanz invited the Anderson to join him in his car outside a restaurant in nearby Skiatook that afternoon, where they could speak privately. Unbeknownst to Anderson, Glanz was recording their conversation with a state-of-the-art, reel-to-reel tape recorder hidden in the trunk of his car and a microphone embedded in the dome light. Once Anderson got in, Glanz activated the recorder by discreetly flipping a toggle switch under the dash.

The private investigator spoke frankly, explaining he didn’t believe Anderson’s story. Glanz had not only gotten in to sketch the crime scene—an examination that shot several holes in Anderson’s tale—he had informants on the inside of the investigation who were passing him information.

The private investigator spoke frankly, explaining he didn’t believe Anderson’s story. Glanz had not only gotten in to sketch the crime scene—an examination that shot several holes in Anderson’s tale—he had informants on the inside of the investigation who were passing him information.

That led him to the conclusion that Anderson had killed his employer, likely in self-defense after Mullendore had shot him, Glanz told his passenger. The investigator revealed that his study of the blood splatters made it clear that Anderson had stopped at the top of the stairs and took the shots at the door. Law enforcement officials should have figured that out too, Glanz told him, but they had botched their investigation, and physical evidence that could have been used against Anderson was not collected.

“They might charge you with the crime, but I don’t see how there’s any way they can prove it,” Glanz says on the tape.

The detective advised Anderson to get an attorney. He told Anderson that if he turned himself in and explained that he killed his boss in self-defense, he likely would be exonerated.

“I just guarantee you could walk out of that courtroom,” he tells Anderson on the recording.

Anderson mostly sat and listened, neither confirming nor disputing Glanz’s version of events. Finally, he was moved to wonder about his chances.

“How would a case look against me, the way it stands?” he asks on the recording.

“It looks like you’re guilty,” Glanz shoots back, then adds a touch more gently, “It looks like you’re lying, definitely.”

Glanz and Anderson would meet again on January 12, 1971, at a Tulsa eatery. The mood this time was lighter, as Glanz recalled, with the two men

sitting for three and a half hours, drinking coffee, laughing and chatting.

By that point, Glanz knew the crime scene had been hopelessly contaminated. Mullendore’s body had been removed before any photos were taken, no scrapings were taken from his fingernails, and his hands were scrubbed by funeral home attendants before a paraffin test could be conducted that would have detected the presence of gunpowder, an indication that he might have fired a gun.

Additionally, little, if any, physical evidence had been collected. Few fingerprints had been lifted, and no hair or blood samples were collected—all standard procedure. Worst of all, the body had been embalmed before an autopsy could be performed.

Glanz had one more meeting with Anderson on June 1, 1971, at a Bartlesville nightclub. The two met inside for a drink, then moved to Glanz’s car to speak privately. Again, Glanz recorded their talk.

Inside the club, Anderson had told Glanz that only three people really knew what happened the night of the murder. The investigator seized on that revelation when they got in the car, asking Anderson if he was opposed to taking a lie detector test.

“No, I’m not opposed to it. I’d like to clear myself,” Anderson says on the tape before backing away from that pronouncement, explaining he no longer appeared in danger of being arrested. “On the other hand, I wouldn’t want to stir it up again.”

The two chatted for a few more minutes. Then, for the first time, Anderson let slip a hint that he was not being completely forthright.

“I’m not hiding nothing from myself or nobody else,” he says on the recording. “I might know something I’m not telling, but I’m not going to tell it in New York if I don’t tell it here.”

Glanz steered the talk back to the murder, hinting that only Anderson could solve the mystery.

Glanz steered the talk back to the murder, hinting that only Anderson could solve the mystery.

“I’ve told you way more than I’ve told anybody else,” Anderson says before offering another observation that came perilously close to the truth from

Glanz’s perspective. “You may have the best tape recorder in the world going.”

Anderson joked that he would reveal the whole story on his death bed.

“If I got shot through the heart, Gary, come see me quick,” he says on the tape, chuckling.

Glanz reluctantly let the conversation draw to a close. The two parted ways warmly, not realizing it would be 37 years before their paths crossed again.

Fading into the Background. Public fascination with the case eventually waned, returning only with the resolution of the insurance claim in December 1971 for $8 million—enough to stave off the creditors and save the ranch from foreclosure. Glanz would recall seeing the sum listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the largest claim ever paid on an individual death in the history of the U.S. insurance industry.

The murder investigation expired with a whimper. In February 1972, a grand jury was convened to look into the killing, but it ended its term without issuing any indictments. Anderson had escaped testifying by moving to Kansas and refusing to answer his subpoena.

By then, Glanz had lost touch with the ranch hand. Periodically, he would hear snippets of information about him, especially after Anderson was convicted in a marijuana-growing scheme by Kansas officials in 1990 and jumped bail, disappearing without a trace.

Still, Glanz never stopped thinking about what really might have taken place the night of the killing—even when he was informed by Linda Mullendore’s attorneys after the settlement was reached that his services were no longer required. In spite of his dismissal, he was convinced he could get Anderson to tell him the true story of the rancher’s killer and put the mystery to rest—for the sake of history, if nothing else.

While the private detective’s career thrived, Anderson’s scrapes with the law continued until, in 1990, staring down a lengthy jail sentence because of the pot-growing conviction, he went on the lam. He slipped across the border to Mexico, then headed north to Montana, where he assumed an identity and found work on a bison ranch owned by media mogul Ted Turner.

That may have marked the end of the two men’s history together if destiny had not brought them back together in 2008. This time, they would, as Glanz long had hoped, sit down and have an honest conversation about the circumstances of E.C. Mullendore’s death. It was, as Anderson would reveal, a story that included a twist no one had envisioned.

BIO – Mike Easterling

Mike Easterling is a veteran editor and reporter who has worked for newspapers in Oklahoma, New Mexico and Colorado during his career. His stories have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Denver Post, The Arizona Republic and dozens of other publications across the country. He lives in San Juan County, New Mexico.