Beyond the Wall of Fear

By Ash Saunders

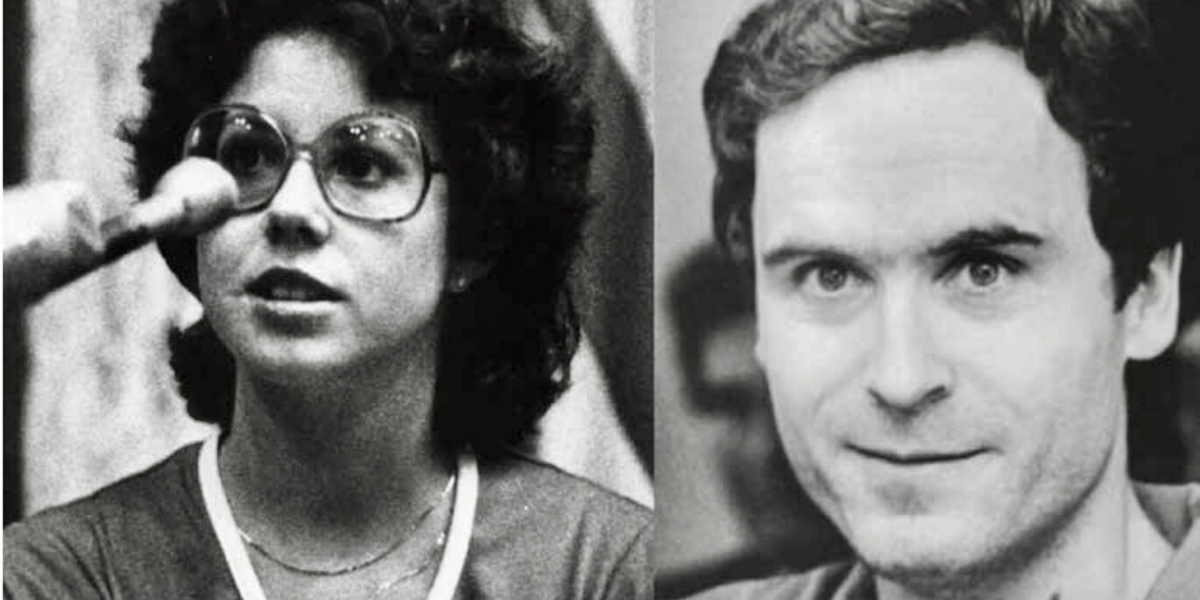

A Conversation with Kathy Kleiner on Ted Bundy

This is the story of Kathy Kleiner, one of the few survivors of a deranged killer: Ted Bundy.

She was not just the girl next door, nor just a college student growing up in the 1960s and ’70s. Kathy Kleiner was and is an embodiment of strength and humanity. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to hear her story in her own words. Part of Kathy’s inner strength to endure was built on her childhood.

She dealt with much hardship in her early life. Her father died when she was five years old. At 13, she was diagnosed with a dangerous illness, systemic lupus erythematosus, a serious form of lupus that attacks the organs. Yet, even during the three months that Kathy was in the hospital for lupus, she remembers sparks of joy. Her sister would take her “in a wheelchair running really fast down the hall.” She still remembers the prayer circles friends and family had for her in the hospital.

After spending seventh grade homebound, Kathy went back to school knowing that she “couldn’t do anything strenuous,” as being under any kind of stress could reactivate her illness. So during gym class, she would help in the school’s office and search for other avenues of joy.

In her freshman year of high school, Kathy discovered theater. She said theatre took her in a “positive direction from where I was. Within the first year it was like, who was that back then?”

Kathy made many friends in theater, including her future husband, Scott.

“I put up a wall between me and that sick kid,” Kathy told me. “Theater was in front of me, and I was enjoying the hell out of it!”

Kathy moved on from the pain she had felt the year she was diagnosed with lupus by enjoying her life and filling her days with friends she made in theater.

“It was just forward; it was just go!”

Theater taught Kathy a lesson that she did not forget: moving beyond her past.

“Those four years made up for that one year when I was at home. . . The little girl went away. That sick little girl. I was so forward-thinking at that point.” Kathy built a mentality of moving forward and not letting anything or anyone define her outlook on life. She would later use this resilience to move on from Ted Bundy’s attack.

As Kathy was living her life to the fullest and reaching her potential, Ted Bundy began his murder spree on the west coast. His first reported murder was in February 1974. The victim was Lynda Anne Healy, a University of Washington student.

He then killed 16 other girls, their ages ranging from 12 to 26: Donna Gail Manson, Susan Elaine Rancourt, Roberta Parks, Brenda Carol Ball, Georgeann Hawkins, Janice Anne Ott, Denise Naslund, Nancy Wilcox, Melissa Smith, Laura Ann Aime, Debra Jean Kent, Caryn Eileen Campbell, Julie Cunningham, Denise Lynn Oliverson, Lynette Dawn Culver and Susan Curtis.In November 1974, Bundy attempted to abduct Carol DaRonch.

He was caught because of incriminating evidence found in his car: masks, gloves, rope, a crowbar and handcuffs. He was charged with the abduction in August 1975.

When Bundy was being charged for the kidnapping of Carol DaRonch, Kathy was starting her freshman year at Florida State University (FSU).

Kathy was accepted to several universities, but she chose FSU because of the distance from her family and the new opportunity for independence.

“A lot of my friends were going there as well,” she said. “But that was my going to as far away from Miami and still having in-state tuition.” Kathy was looking forward to the next step in her life and exploring what she wanted to do. She continued theater for a semester, but decided “that I didn’t need to be there.”

Kathy had used theater to move on from her past, to have fun and enjoy her high school years. She felt that it was time for her to move on with her interests, and decided to join the Chi Omega sorority.

Meanwhile, Bundy was convicted for aggravated kidnapping and attempted criminal assault in the DaRonch trial. In October 1976, he was charged with the murder of Caryn Campbell and was moved to Aspen’s prison. He escaped twice in the next year. The first time, in October, by jumping out of a second-story window. He was found in a week.

The second time was in December 1977. After losing enough weight and working out, he slipped out through a light fixture hole. Bundy then made his way toward Florida while Kathy was starting a regular second semester at FSU.

I asked Kathy if she felt safe on campus or if she was aware of Bundy and his escapes before the attack.

“As far as feeling safe, I totally did,” she said. “I was really in my bubble, you know, we all were in a bubble. The sororities, toga parties and just doing anything we wanted—to go at midnight, go to the grocery store if we wanted to. It was like everything was different and everything was wonderful.

“I don’t remember anyone ever talking about anything like that. I lived in the dormitory my first year, and they were all about being careful when you walk to the car, walk on campus at night. It was just the normal security things. Walk to the car with two people.

Just normal things.

“No one I knew ever talked about that [Bundy, or any other deranged killer on the loose], so I would say it was not on my radar. It may have been somewhere around the university that people knew about it. But in my group of people, everything else seemed really far away, especially my parents.”

That bubble was in place the day before the attack. It was not a normal day, but a delightful occasion. There was no dark foreshadowing of what was to come, no trepidation or fear; just life.

“The day before the attack, there was the wedding,” Kathy explained. “There [was] a couple that got married: one was a senior and the other just graduated. We went to their wedding, which was like noon or something on Saturday. Dressed up and everything. With [a] small church ceremony and then their reception, which was outside. We all brought a dish because no one had any money back then, so we all brought food and did their reception.

“I remember going back to the sorority house and chatting with everyone and did all this and the other and then ended up going upstairs. I was going to change to go out and then I said, ‘I don’t feel like it. I have a test to study for,’ so I stayed home.”

Kathy decided to study in her room with her roommate, Karen. Karen was on one side of the room on her twin bed, and Kathy was on the other side of the room on hers. They studied until about 10:30 p.m., turned off the lights and went to sleep.

Kathy and Karen had a typical-size dormitory room in the sorority house. There were eight or 10 rooms, with rooms on each side of the hallway. Straight down the hallway, on the left side, the first room belonged to Margaret Bowman, the first victim of Bundy in the house. The room across from hers was Lisa Levy’s, the second girl to be attacked.

Kathy described how it felt to walk into her room.

“So when you walk into the door, it’s the same size as a dorm room, kind of small. On each side of you are dressers right up against the wall. You walk in, passing the dressers opposite each other. You walk a little bit more and our twin beds, it was one on one side of the room, [the] side directly next to the wall where the dresser was, and the other twin bed on the other side of the wall.

“We had gold carpet, and in between the beds, we had a small trunk, like a footlocker, just one of those small trunks that we put stuff in it. It wasn’t a high trunk, it was real low, about three feet high. Against the back wall were windows, a bank of windows. The whole wall was windows, and our room was in the back of the house, so it faced the parking lot. Our window shades were always open because we hung plants on the curtain rods.”

Around 3 a.m., Bundy came into the house through the back door, where a lock was broken. He picked up a log from the firewood beside the door and went to the second floor, where he murdered two of Kathy’s sorority sisters before opening Kathy’s door.

Half asleep, Kathy heard the door open and shut as it gently brushed against the carpet. The next thing she heard was someone tripping on the trunk that was sitting close between the beds. Because the intruder didn’t know the trunk was there, he stumbled over it as he walked toward the two beds. The noise completely woke Kathy up, and all she saw when she looked around the room was a black shadow. He was close enough for her to see the dark top and clothes that he was wearing, but she couldn’t see his face in the darkness of the room. Kathy remembers “watching him lift up his arm, his right arm, up over his head, and he had a log in his hand.”

Bundy slammed the log against her head, breaking her jaw so that it was hanging on by a joint and ripping the flesh of her cheek. She almost bit her tongue off, and the cut opened her cheek so you could see inside her mouth from the corner of her lips to her ear.

“I think with him it was the first blow that was the killer,” Kathy told me. “He didn’t continuously hit women; it was like he hit a woman, and it was so strong. My roommate heard this noise, and so [Bundy] turned around and tripped over the trunk and beat her in the face.”

She said, “It must have been seconds, but it seemed like hours.”

Kathy remembers sitting up in her bed and screaming, “Help me! What’s going on!”

“In my head I was screaming,” she explained. “But all I was doing was making gurgling noises because I couldn’t, I couldn’t communicate because my jaw was already hanging. In your head you’re saying something, you’re doing anything.”

Bundy came back to Kathy.

“He came back across to my room, my side of the bed, and I saw the log lift up again.”

At that moment, a car pulled into the parking lot and, because her window shades and curtains were open, the light shone right into Kathy’s room.

“Then I could see him standing there all in black, standing there with the log as he’s looking out the window. It startled him, so he looks out the window. He’s all illuminated, our room—it’s like this bright light. Alleluia! Like one of those feelings of delight opens up.

“It spooked him because he did not hit me again. But he turned and ran…at that point, he ran. I still, I, I’m kinda cringing my eyes tightly shut waiting for the next blow. And he ran out of the room. I remember delight went away. The room got dark again.”

In the dark room, Kathy was not sure if Bundy would return.

“I don’t know how long it took until the police officers and paramedics came,” she said. “It seemed like hours. But I remember the first time I saw the police officers standing next to me, I felt so comforted. Now, I know this isn’t coming back, this isn’t going to happen again, and I just felt safe. That’s what they do. They make you feel safe, and he did, he really did.”

Once the paramedics came and Kathy felt safe, she went in and out of consciousness. After she was checked medically, she was hypnotized so that she could remember the details of the night.

“I never had any therapy or anything after the attack,” Kathy said. “I only saw those psychiatrists in the hospital.”

Kathy asked the hospital psychiatrist if she needed to see anyone, and they said to see a therapist or someone when she needed to.

“I just never needed to talk to anybody. I was dealing with it along with my parents and my sister. We were open about it. I watched a lot of soap operas because Mom didn’t want me watching the news. We would play games and a lot of stuff that wasn’t related to the Bundy story. That’s the way I dealt with stuff. It’s just to face it and move on. And when it goes away, it’s not a problem anymore.”

I then asked Kathy how she was affected by the attack.

“Physically, I have TMJ really bad. I’ve had several operations over the years, and I had, I had, one two years ago. I spent so long, and my TMJ gets so bad that I wait until the last minute, till I can’t stand it anymore, because I have another surgery. I’ve had [surgery] on both sides over the years. I usually only have one side at a time because I don’t want to be wired shut.”

The scar on Kathy’s cheek, where it had been ripped by the log, is numb, another remnant of the attack.

I asked Kathy what she remembers the most about having her mouth wired shut for the nine weeks it took for her jaw to heal after being rebroken again for medical reasons.

“I had to have nail clippers. I had them on a chain around my neck, and I always had to have them. There was always somebody who slept in the room with me at night. I wasn’t left alone a whole lot, but not just because of that [the jaw], but my parents and my family wanted to stay with me, so if anything ever happened, if I choked or started to throw up or anything, they’d have to cut my wires. That was kind of a weird situation, you know, everything going on and here I have wire clippers, which is so random.”

Kathy said after the attack, she “didn’t focus that much on the emotional end of it because my mind was on the healing, and so mostly I was just at a place I could tolerate, as far as not being overly emotional about it.”

“Basically, I didn’t even let the emotions come into it because I was physically trying to heal,” she told me.

I then asked her about the fears that were brought on by the attack.

“During that time, I don’t know if it was my feelings or people asking me, ‘Are you OK around strange men?’ and everything. I don’t think that would have been an issue with my own mind, that it would have bothered me, but it started bothering me.

“So right after I got my mouth unwired, because of this angst and this fear, I went to work at a lumber yard in Miami. I figured that was the place I would see the most men … I worked at the cash register in the front and the people behind the desk, in my situation, they were always kind of looking out for me.

“After a month or so doing that I said, ‘Well, I’m over this.’ So I quit. It was just a means to the end because I needed to confront and overcome that.”

Kathy used the resilience she learned from theater and overcoming lupus to push past the fear. But she still had to overcome one fear that was infecting her from the attack: she now had a fear of hospitals.

“I just froze,” she said about going to a hospital. “I just couldn’t go to the door. I couldn’t do it. So I’d sit outside on the bench—not even in the lobby, I couldn’t even go that far. This bothered me because you have friends or babies and stuff, you want to go in. So to overcome that obstacle or that fear, I went to human resources and got a job working in the hospital, and I worked there 18 years.”

Kathy used what is known as exposure therapy, which is suggested for people with phobias. Exposure therapy is when someone experiences or is exposed to what they are afraid of. Kathy said, “It was wonderful. One of my most paid jobs that I’ve done. It goes away, and then I look for something else to do.”

After the attack, Kathy felt more compassionate for other people, and she learned to accept help and support. She said she “learned that it’s OK to need people.”

“When I was going through it,” she explained. “At first I was like, I don’t need your help, I could do it myself. Then I realized that people around you need to be doing something, they want to help you. So instead of saying I can do it myself, I say ‘Yes, thank you for helping me.’ It would make them feel good. It was letting them help me, although I didn’t need it.”

Kathy is even able to help the tourists that wander around her city, asking them if she can help them take photos or just being understanding.

“I just found out that I have more compassion for people now. I tend to feel a little bit more, after all these years, more compassion. I just want to talk to people more and, you know, help them with a problem, get through anything if I can, or just talk things over. But I feel more compassionate.”

Kathy took what happened to her and grew it into an empathy for and understanding toward the world.

I asked Kathy if the attack affected her outlook on humanity and the people that surrounded her.

“No,” she said. “I don’t think so. “Because I think it was an isolated instance. I know that all the women that he killed, it wasn’t isolated to him. But in my situation, I was just lying there in bed sleeping when he came in. So it doesn’t change my outlook on people. Most people are good.

“I mean, I’m aware of things, if I’m walking or anything, if I hear somebody behind me, I’ll just stop and lean against a wall and let him pass. I tend to be more aware, and I reach into myself to get myself the strength to do it. I don’t hide from anything.”

Kathy was always looking to see how she could move beyond the obstacles in her way. With Bundy, she didn’t let doubt about humanity creep into her mind. She saw Bundy as what he was: an isolated incident.

Kathy described going to the courtroom during Bundy’s trial and looking at him from the witness stand.

“I came in the back door by the judge. I sat down. I get settled and look out at the courtroom. And there’s Bundy sitting at the defense table, not too far away from me—it wasn’t a huge courtroom. He’s sitting there and leaning back, and I can see that he’s leaning on his arm with his hands holding his chin and the finger is up by his cheek. Just sitting there like he always did. And he’s looking at me and I’m looking at him. I don’t take my eyes off of him.

“The prosecution asked me questions, and I don’t remember what they were. The defense asked a couple of questions and then said, ‘Is this the man you saw in your room that night?’ I had to say ‘I don’t know’ or ‘no.’ It was just so sad because I wanted to help convict him. I wanted to be there, a part of the conversation.”

Kathy is a part of the conversation now, making her voice heard and telling her story.

“After the stare down,” she continued. “I left the witness stand, and I went back to the courthouse and almost threw up. I wasn’t afraid of him, or afraid he was going to come get me or anything. I wanted to show strength, that now I had more power than he had. He used to have the power over women, and it just kind of felt good that I was able to do that.”

I asked if she was interested to see if he was convicted.

“Not so much,” she answered. “I’m sure it was on every channel but, once again, in 1979, it wasn’t top of my list of things to do. I was still trying to walk away from it. . . It’s not that I wanted to see justice happen, if he was going to get juiced or not. It was more like, just, you know, have a good day and you’ll find out what happens when it happens.”

Kathy was able to move on from the attack without the reminders that the media provided.

“I wasn’t following the TV or anything. That wasn’t part of what I was going through.”

She saw the trial as, “What would happen would happen, then I was going forward.”

I then questioned Kathy on what she was doing the day Bundy was convicted.

“I don’t even remember what I was doing when he was convicted,” she replied. “It wasn’t a big thing that I had to follow; it wasn’t like he had made an impression on me.”

She added, “I remember hearing about it, but I never thought that much about it. I heard about it, but like I said, I was trying to go forward. . . I didn’t have a feeling that I had to know at that point. I found out when I found out.”

I asked Kathy how it felt to become an inspiration to so many people.

“It’s funny,” she answered. “Because in the beginning of all these interviews, you pick up your hands like you got to cup some water. That was my story.”

“You open your arms as wide as you can,” she continued. “That’s my story now. It has reached so many people.”

Kathy told her son, after sharing her story, “It’s just me. Just one story, but it’s bigger than that now.” Before telling her story to the audiences she reaches today, Kathy wasn’t sure what to tell her son.

“The birds and the bees and Bundy just didn’t come up.” But for Kathy, her story is just that: hers.

“I don’t know if I can help people understand that, just because I went through something and this is the way I handled it, that not everyone can do something like this. But they can try … It’s a box. You step out, you walk away a little bit, or do something and get out of that box.

“To go through all of this, it was like I was reaching deep down inside of myself and finding that strength and pulling it up and out and physically and mentally looking at it.

“And it’s kind of shaky sometimes, of course, I’m not 100% on everything. Things get me down, but I know that strength. I just want other people to know that they have it too in their own way. Whatever they’re facing, they can walk through it because they have that power. I have the power to do it.”

I asked Kathy about Bundy’s conviction and sentencing.

“He was to be executed,” she said. “That I wanted to happen, you know, just do it and get it over with and keep going. And then he kept getting stays of execution and stays of execution over the years.

“Whoever makes that decision and says, ‘Yes, he deserves a stay’ and whatever, I wonder if they have a daughter … It just was mind-boggling to me that so much could happen and Margaret and Lisa were killed, and all these other women were mangled … They want to let him live longer and all for something. The conviction that was so strong with the bite marks and just no lack of possibility of it not being him.”

“I became very and weirdly upset,” Kathy says about the day of Bundy’s execution. “And I remember I cried and I cried a lot, and it seemed like I was crying more for Margaret and Lisa, for all the other women, all the ones that he killed. I was crying for them … getting it out of my system, not so much for me. I can’t even remember why I would cry for me.

“It was just all for them, and Scott said I was wailing. After that it was like, you know, I got it out of my system.”

After the execution, Kathy went to breakfast with her future husband and went shopping. The day was not defined by Bundy. His mark on her life became a memory that Kathy has used to heal and grow beyond being a victim.

I then asked Kathy how she felt about Bundy after she found out what he did to her friends and all the other women.

“I just hated him more.” Every time Kathy heard something, it would jab at her heart a little harder.

“I couldn’t, I can’t forgive him, and I won’t forgive,” she said. “[It] feels like it’s not just for me, it’s unforgiving for the other women because they’re not here to … I feel like I’m speaking for the other women, that for me to forgive, it seems so lame.

“Each time [she learned more about Bundy], it just solidified that he was the one. I hear about it, I’m talking about it, and it’s a healing process because I’m getting it out of my system by talking about it, and therefore I’m not hiding from it.”

Recovery for Kathy and her life after the attack was challenging, but Kathy always moved forward. She was married within six months of the attack, though the marriage later ended in divorce.

When diagnosed with lupus, she was told not to have children. Today, she has a 38-year-old, healthy son.

During the time Kathy was married, she worked as a teller in a bank. There she was robbed at gunpoint and went back to work the next day.

After her divorce, Kathy was a single mother for five years. In 1989, she married a good friend from high school, Scott.

At the age of 34, she was diagnosed with stage two breast cancer and had a radical mastectomy. It took several surgeries to complete the reconstruction process. Again, she was given chemotherapy.

Kathy also had two miscarriages, both in her second trimester.

Kathy lived in New Orleans in 2005, and lived through Hurricane Katrina.

Since the attack in January 1978, Kathy has never been contacted by any Chi Omega sister.

Kathy continues to be cheerful, joyful and compassionate.

“I think that I’m in a good spot in my life and in my world,” she said.

Kathy told me that recovery was, “taking baby steps toward that dark figure, until it was behind me … I’m not going to pull a wall in front of me without looking around it or going through it.”

The traumatic event Kathy endured did not mold her. She defined herself. She built herself up by facing challenges to better herself. Her experiences are an unfolding beauty of perseverance against trials and tribulations—a quest for life, a pursuit of happiness and a joy to overcome hardship. She values human life and humanity, in stark contrast to Bundy. Kathy sees people as people, and holds out her arms with her story.

Kathy’s story is not only about her. It is for everyone who has experienced trauma and challenges. It is a story of fear, darkness, pain, inner strength, inspiration and resilience—the resurrection of humanity. Kathy takes us beyond the story of trauma, beyond the wall of fear to show us how to see, so we too shall live.